The fascinating Propaganda leaflets of the south-west Pacific and Japan in WWII

The fascinating Propaganda leaflets of the south-west Pacific and Japan in WWII

Published in Antiques and Collectables Magazine, December 10, 2020.

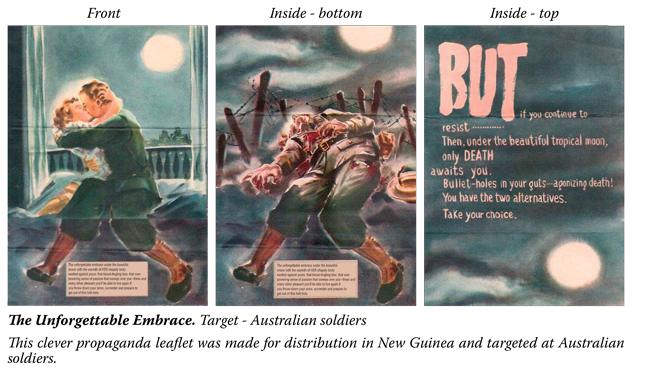

Target - Australian soldiers

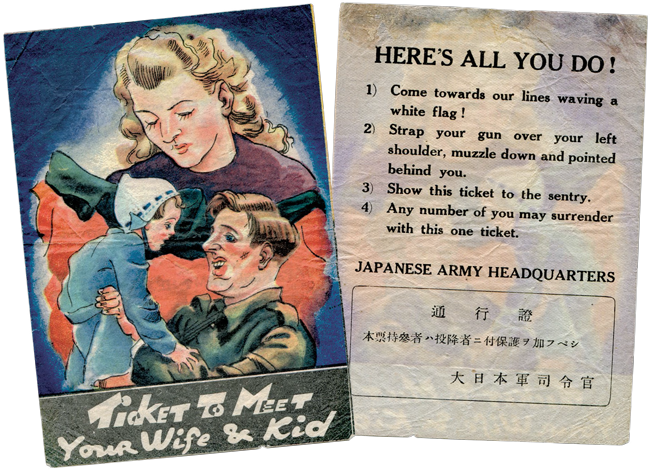

Deep in the humid jungles of New Guinea, the Allied troops duck for cover as another plane approaches. Bombs are dropped and a shower of paper explodes overhead. As the plane’s roar fades into the distance, the troops emerge to find thousands of leaflets strewn across their path. Their heightened adrenalin and sense of fear is quickly dampened by depression and regret as they read the latest message from Japanese Army Headquarters: ‘Ticket to Meet your Wife and Kid’. The message is accompanied by an illustration of an Australian soldier holding a young child with mother behind. The reverse of the leaflet outlines instructions for surrendering to the Japanese.

As the Japanese headed south towards Australia, they dropped numerous paper bombs carrying messages of terror, attacking the Allied troops on a psychological level.

There were common themes used to target the emotions of young Australian and Allied soldiers, including fear, starvation, anger, sadness, distrust, anticipation, love and remorse.

Often the leaflets told an emotional story, beginning with love and happiness only to reveal a sinister and dark ending. A seemingly happy soldier in love in one instance, being blown up and disfigured in an another. Indeed, political correctness played no part in telling the raw and emotional stories.

There were many thousands of leaflets printed and dropped in the jungles of New Guinea. They range from simple black and white, text-based surrender leaflets to elaborate full colour and multi-page works of art.

Target - Japanese soldiers

Propaganda leaflets were powerful psychological weapons, used to fight the Japanese both in the jungles of New Guinea and the South-West Pacific and in homeland Japan. The notorious Japanese imperial soldiers were known for ‘harikari’ rather than surrendering, but some did surrender and possibly due to the effective leaflets made in Australia.

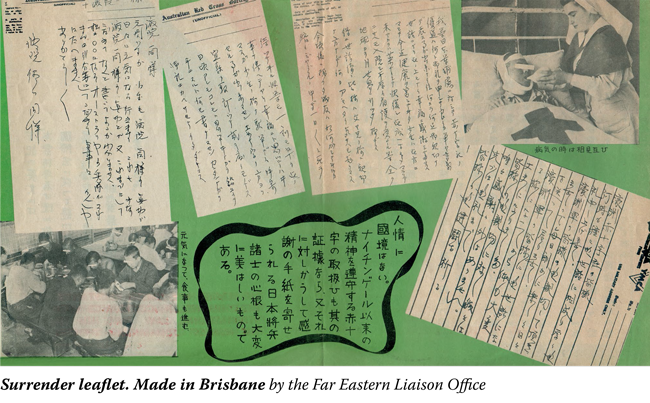

The Military Propaganda Unit of Far Eastern Liaison Office (FELO) was responsible for creating numerous propaganda/surrender leaflets in WWII targeted at the Japanese heading south. The task of creating the leaflets was not as easy as expected, mainly due to the language barrier and lack of resources. Many Japanese residents in Australia were interned at the time and could not be trusted to develop campaigns against their own country. The challenge was felicitously met by Charles S. Bavier, from the propaganda team in Brisbane. Charles organised the printing of leaflets in Brisbane by private companies but soon realised they could not meet the demand, so a new printing factory was established. Charles didn’t have access to any Japanese typefaces so he ended up handwriting the intricate Japanese kanji using a fine pen and paintbrush. Some leaflets contain hundreds of characters which was an enormous task for the Englishman to create. Taking this into consideration, the leaflets are indeed works of art. Unlike the Japanese leaflets, the Australian ones did not draw on sinister themes of sex and death but rather compassion. They mostly portrayed Japanese soldiers being treated well, given nutritious meals and receiving medical treatment.

Target - Japanese civilians

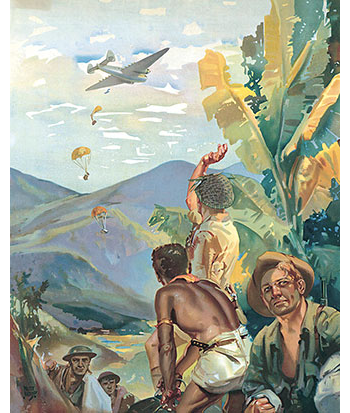

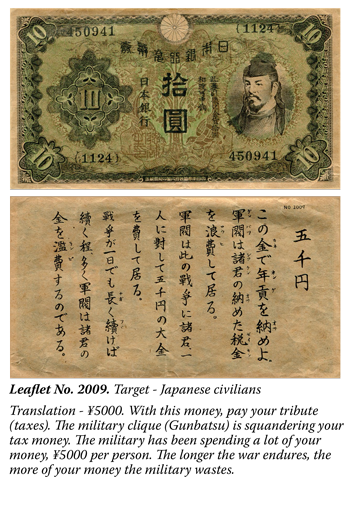

In 1945, leading up to the Japanese surrender, Allied forces targeted mainland Japan with daily paper bombs of propaganda leaflets. B-29 bombers loaded with bales of leaflets, dropped hundreds of tons over Japan, often spreading out over entire cities. It is unknown how many varieties of leaflets were made. Some were low quality and so poorly translated they were unreadable and would have had little impact. Others such as the ¥10 propaganda notes, were instrumental in turning the tide of war.

The 10 yen leaflets describe how the Japanese military has wasted money on waging war against the world’s strongest country; commodities, food and clothing are now scarce, rationed, of low quality and hard to obtain; and the Japanese people are feeling the full affects of Japan’s squandering of their tax money.

The ¥10 propaganda notes were well-planned and carefully drafted by the Psychological Warfare Branch in Hawaii. The front closely matches the design of ¥10 banknotes that were placed into circulation at the end of 1943, so were familiar to the Japanese people. The clever use of an actual ¥10 banknote design on one side made these campaigns very effective. ‘Money’ rained from the sky almost daily. Who could resist picking up ‘money’ off the street? As the War was nearing the end, the Japanese people started to believe the messages that were delivered on these leaflets. According to a number of Japanese officials interviewed after WWII, these leaflets were some of the most successful of all, in assisting a peaceful Allied occupation.

Collecting

Collecting propaganda leaflets is enjoyable and rewarding. It's best to restrict a collection to one type or region rather than trying to build a general WWII collection. Even a small collection of a few related leaflets can form an impressive display that is visually stunning, intriguing and a great investment.

Propaganda leaflets can be found for as little as $20 for black and white and non-illustrative examples. Cheaply produced and vast in quantity they are novel and interesting. The ¥10 propaganda notes range from $40-$100 each depending on the kind and condition. There are 4 kinds in the set, all carrying the same serial number (1124) 450941. The leaflets created in Brisbane are popular and range from $80–$200 depending on the rarity.

For the serious Australian collector, the colourful and illustrative leaflets made by the Japanese and targetted at Australians are the most highly prized. They have shown solid growth over the past few years yet still remain relatively inexpensive, considering their historical significance. Good examples range between $100–$250 depending on the quality and imagery, with the rude and sinister, commanding a premium. These will inevitably increase in value as demand increases in the coming years, moving towards the most significant anniversaries of World War II.

Gregory Hale